Strategy | Discovery

Written by Etienne Yuan

July 6, 2022

Innovating within a business context

Seeing innovation management clearly through first principles

The subject of innovation is a uniquely modern preoccupation in the contemporary C-Suite, but if John Wanamaker sat in one today, one could surely picture him paraphrasing this over a century-old quote of his: Half of the time, innovation frameworks work, the other half they don’t. The problem is, we often don’t know which half, or why.

Cometh the fad, cometh the framework mongers. Frameworks, however, only work when conditions on the ground replicate those for which they were specifically devised. This is especially true for frameworks that take the form of prescriptive, checklist-based processes. In fast-changing environments, that is far from guaranteed. And instead of providing clarity, the unthinking and wholesale application of frameworks only adds to the fog of confusion.

Although it is more demanding at the start, a first principles approach is arguably more robust and generalizable. In this article, we’ll dive into the business fundamentals that constrain the discipline of innovation within a corporate context, and cut through the fog of seemingly contradictory or irrelevant frameworks.

We aim to achieve this clarity of vision by examining the economics of innovation, and build our model, or framework, first principles-up.

The business of innovation

In 2020, OECD countries invested about 2.68% of GDP on research and development activities. Notably, Israel spent 5.44% of GDP on R&D; the US, 3.45%; China, 2.40%; and the EU 2.20%. Of the 1648 billion US Dollars spent on R&D in the OECD in 2020, private enterprise accounted for 71.5% (OECD, 2021).

So, innovation is big business. It is also risky business. That nine out of ten new ventures fail is a widely accepted rule of thumb in the venture capital community. Given this 90% probability of failure — or 10% probability of success, if you’re a glass-half-full person — many practitioners advocate for a venture capitalist approach to managing risky innovation and new product development in the corporate setting.

What does that mean?

Innovation as a business

There’s plenty of innovation happening in the not-for-profit sector: Universities, government agencies, think-tanks, etc. However, at 71.5% of GDP, the bulk of the investments take place in the for-profit sector. And what characterizes this type of investment, is that organizations expect to be rewarded for providing a valuable good or service with a profit.

Profit = Revenue – Cost

As we have seen, new ventures are risky. Therefore, we can further expand this definition to state that those who undertake that risk expect to be rewarded for doing so.

Profit = Risk ( Revenue – Cost )

But what is risk?

Defining risk

Much has been said about how we live in a knowledge economy, and how we need to build learning organizations to thrive in it. Cliché, but also true.

In the context of the knowledge economy, risk is that which we don’t know.

Profit = Known ( Revenue – Cost ) + Unknown ( Revenue – Cost )

And learning organizations are those that are capable of transforming unknowns into knowns most efficiently and effectively.

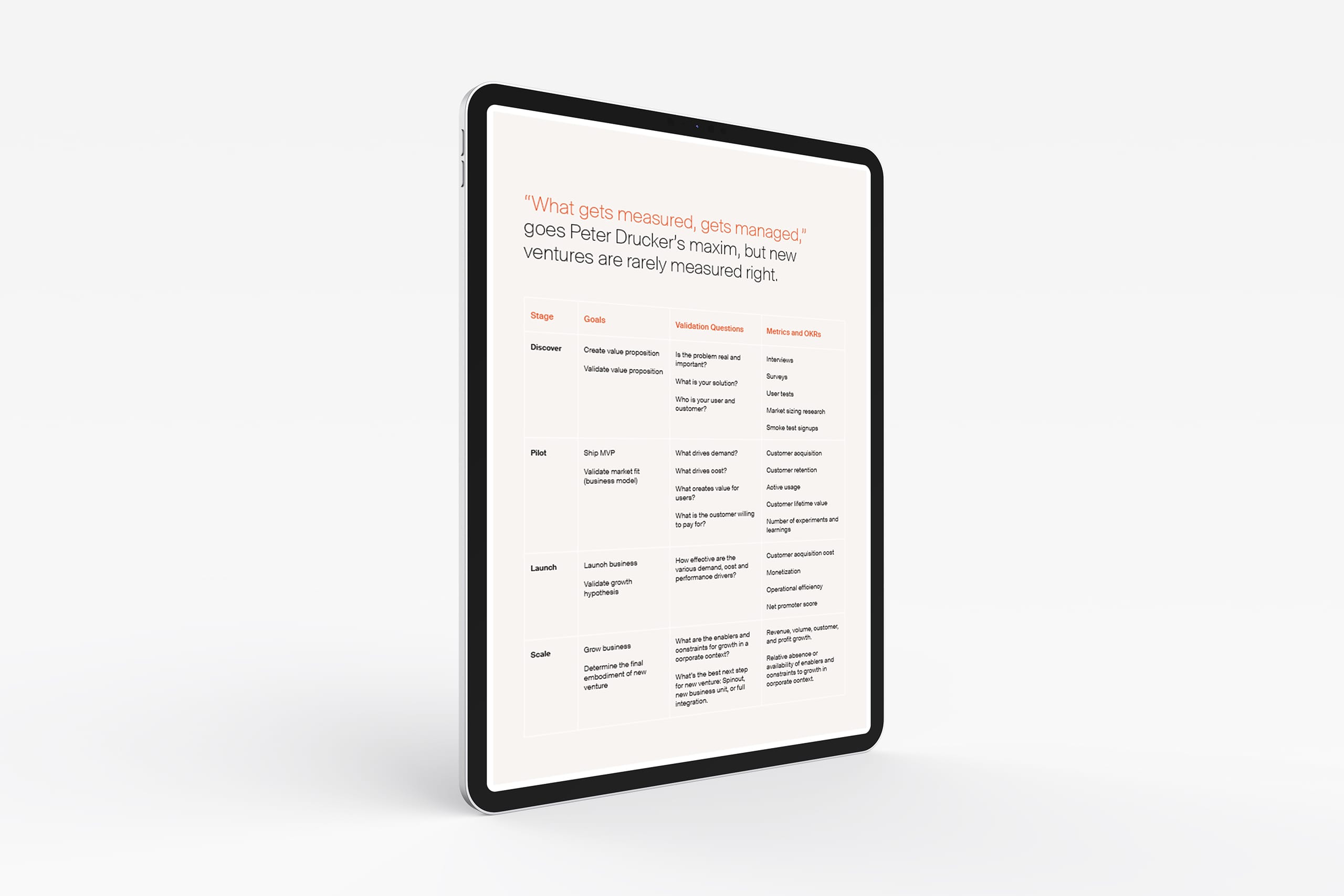

Knowledge-Based Risk Management

Risk is what you don’t know, and knowing things comes in two flavors: Awareness and knowledge. You may know that something exists, but not its inner workings. That’s awareness. If you know how it actually works, that’s knowledge.

Plotting this in a two-by-two yields four quadrants.

- Known knowns: Things we know that we know

- Known unknowns: Things we know we don’t know

- Unknown unknowns: Things we don’t know we don’t know

- Unknown knowns: Things we don’t know we know

Knowledge-based strategies to manage risk

An effective learning organization identifies the most relevant unknowns, and transforms them into knowns as accurately as possible. An efficient learning organization also does so as cheaply as possible.

We do that by deploying four strategies.

Image: Knowledge-based Innovation Risk Management Strategies, Etienne Yuan

- Known knowns: Project Management

If you know everything, then go ahead, put it into your Gantt chart, and waterfall your project to your heart’s content. However, if we go back to our 90% probability of failure, it would be reasonable to assume that most of the knowledge is to be found in the other three quadrants, awaiting discovery. That’s what the other three strategies are for. - Known unknowns: Hypothesis Testing

This is a staple of the Scientific Method. If you know what questions to ask, you can put forward a hypothesis and then test it. Depending on the result, you either find what you hoped for, or alternatively, as Edison used to say, you find a new way that doesn’t work. Either way, you added an item to your knowledge library. - Unknown unknowns: Diversification

If you aren’t aware that something even exists, then you cannot possibly devise specific ways to deal with it. Therefore, diversification is the most effective way to mitigate this type of risk. The more diversified your innovation portfolio, the better it can absorb unpredictable hits, and the more robust it becomes as a whole. - Unknown knowns: Democratization of Innovation

What may be an unknown within the project team may very well be a known for someone in the wider organization. And a diversity of viewpoints contribute to a more diversified portfolio.

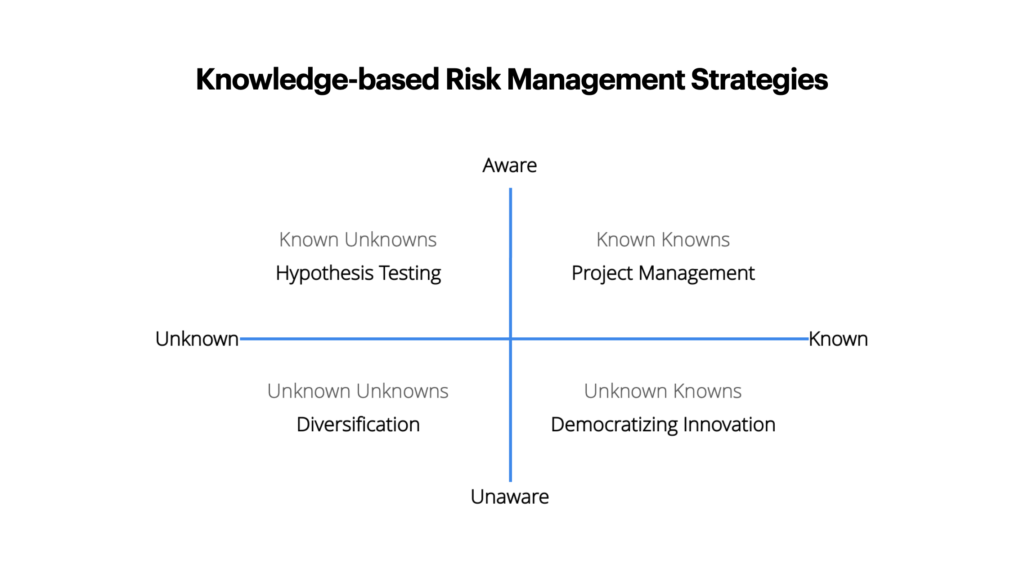

Diversification

The simplest way to diversify is to incorporate a minimum number of different projects or experiments into your innovation portfolio. The question is how many.

If 90% of new ventures fail, then we can say that every single new venture has a 10% probability of success. If you have two new ventures in your portfolio, then you have a 19% probability that at least one will succeed. Three ventures give you a 27.1% probability that at least one will succeed, etc.

1 in portfolio: 10%

2 in portfolio: 10% + [(100%-10%) * 10%] = 19%

3 in portfolio: 19% + [(100%-19%) * 10%] = 27.1%

…etc.

We plot the points in a cartesian map, where the vertical axis represents the probability of at least one successful new venture, and the horizontal represents the number of new ventures in the portfolio. The result is a parabolic function that approaches, but never quite reaches 100%, because of diminishing returns on diversification.

Image: Innovation Risk vs Size of Portfolio, Etienne Yuan

Taking the two reference points of 20 and 32 new ventures in the portfolio, you get, respectively, probabilities of 88% and 97% of the portfolio having at least one successful project. So now, determining the number of new ventures you should pursue becomes an act of balancing risk, cost/budget, and that most crucial resource of all, attention.

Hypothesis testing

There’s an infinite number of hypotheses one can test. However, in a business context, every new venture is underpinned by four relevant hypotheses:

Image: Four Hypotheses Underpinning Every Business Idea, Etienne Yuan

- There is a customer out there,

- who has a need or problem.

- We can create a solution that solves the problem,

- and create a profitable business model around it.

There’s no shortage of popular methodologies designed to test and validate these hypotheses, Value Proposition & Business Model Canvas, Customer Journeys, Design Sprints, etc. So, we will not dwell in those here.

We will spend some time on how to prioritize which hypotheses to test first, though, as it’s a key determinant of how efficiently, or cheaply, we can innovate.

The customer-centric, but prescriptive, checklist-based approach would dictate that you start with testing the customer and her problem hypotheses, then test the solution, and finally design the business model. This would certainly be an improvement over projects that put user-testing last, as typically, the hypotheses grow in cost and complexity to test as you progress in that order.

Following our first principles approach would generalize the criteria for prioritization to be the cost and complexity as measured by the number of dependencies the test has to be performed.

Image: How to Prioritize Innovation Hypotheses, Etienne Yuan

You should start with the lowest-cost hypothesis to test. What good does it do you to incur the spend of an expensive test, have your business idea pass it, only to fail a cheaper test later, and have the idea knocked out of the process anyway?

Moreover, you start with the hypotheses that depend the least on the results of the other hypotheses. Firstly, because they tend to be cheaper to test, but more importantly because, usually, these are the hypotheses whose results the others depend on to be able to be tested. For example, you need to know who your customer is to decide on how to distribute a product, which impacts distribution costs. You also must understand the problem from the customer’s perspective if you want to price the solution right. And you cannot do a business model without either of those two pieces of input.

By a lucky coincidence, a lower dependency hypothesis test is a lower risk for the test itself, but a higher risk for the venture as a whole, given the other hypothesis tests’ dependence on it. So, both criteria point towards the same prioritization.

Democratizing Innovation

Democratizing innovation within an organization invokes Ashby’s law of Requisite Variety. The more complex the environment or problem it seeks to solve, the higher the level of variety that’s needed within the organization. In our model, the benefits of democratizing innovation take effect via two mechanisms.

First, innovation elitism results in a small pool of knowledge lacking in diversity. Very likely, many issues that are unknown within a small ‘elite’ team may actually be known outside it. By engaging the rest of the organization in the innovation process, you stand a much higher chance to uncover those unknown knowns.

And second, as the source of ideas expands, so does the degree of diversification. Even if the number of new ventures remains the same, as it is less likely that ideas be correlated, as they tend to be when they are limited to those constrained by the biases of a smaller team.

The model in action

A simple visualization of the innovation model is that of a funnel.

Image: Managing Innovation Cost & Risk, Etienne Yuan

At the start, a new venture is very risky. And so is a portfolio of new-new ventures. As we start testing the hypotheses, following our criteria described above, the number of unknowns decreases, and so does risk.

The tests conducted also allow us to discern higher and lower confidence bets. We can then lower risk further by culling lower confidence bets. The resulting lower level of risk, and lower number of concurrent projects allow us to increase the level of investment in the remaining, higher confidence bets. You repeat this process after each round of hypothesis testing, until we are ready to go to market with the remaining new ventures.

What goes into the funnel

What specific new ventures will go into the innovation funnel depends mainly on strategy. This will be different for every organization, so we won’t spend time expanding this.

There is, however, an important implication of the 90% failure rate that is implied in our model, and that is that anything that goes into the funnel should have the potential to achieve at least a 10x return on investment. Otherwise, it simply isn’t worth the effort. Although pursing incremental optimizations are a valuable activity, they are better managed within different processes in the organization closer to day-to-day operations.

Real life examples

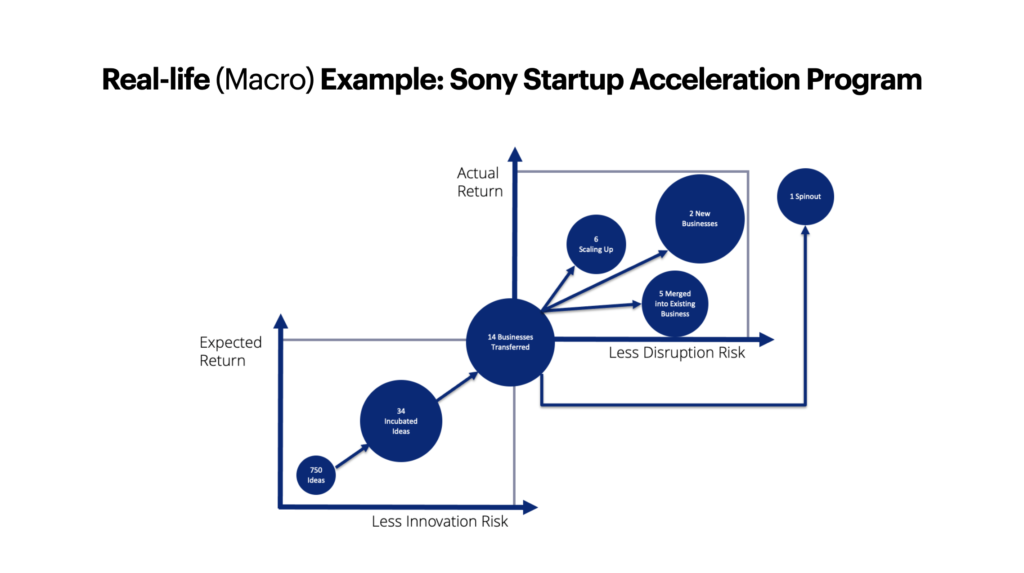

At the macro level, Alex Osterwalder et al.’s The Invincible Company (pages 106–7) provides a detailed description of how new ventures travel through the Sony Startup Acceleration Program’s funnel.

Image: Sony Innovation Funnel in Action, Data from Strategyzer

From 2014 to 2019, Sony started with about 750 business ideas, of which 34 were accepted into incubation. The process further winnowed the cohort down to 14 businesses, of which six are still scaling up in some form, five merged into existing business units, two became business units in their own right, and one became an independent spinout.

A result of 14 actual businesses out of an initial 750 would suggest a very low success rate of 1.87%. However, because Sony has optimized its process, a handful of successes is enough to cover for the cost of the program, and more. So much so that Sony has opened its Acceleration Program to external startups since 2019.

At the micro level, an abridged story of how 3M’s developed Post it® Notes is illustrative.

Image: Real Life Innovation Example: Post It Notes, Etienne Yuan

Initially, responding to the aerospace industry’s need for a stronger adhesive, 3M started developing new chemical compounds. One such compound ended up being a weak adhesive. The company shelved the formula. It wasn’t until a chemist, and occasional choir singer, Arthur Fry, realized the new glue’s potential for people who wanted reusable sticky notes to mark or make comments on documents without damaging them. He tested his hypothesis in the 3M steno typing pool. It was a hit, and an innovation was born.

From a democratic innovation standpoint, it is also interesting to point out that, initially, senior management at 3M did not see the value of the idea. So, it was down to a small lab team that persisted and produced the first prototypes using scrap paper by own initiative.

Conclusions and implications for further action

Innovation in a business context is constrained by the requirement that it satisfy the profit motive. As innovating is a risky endeavor, managing an innovation portfolio requires that the probability of failure be explicit and internalized it into its processes. We assume a generally accepted success probability for new ventures of 10%.

Risk can be understood as unknowns. We’ve identified different strategies to deal with three different types of unknowns: Diversification for unknown unknowns, hypothesis testing for known unknowns, and democratization of innovation for unknown knowns.

Hypothesis testing, in particular, is the mechanism by which ideas travel through the funnel. Every business idea is underpinned by four hypotheses: (1) There’s a customer, (2) who has a problem. (3) We can create a solution to the problem, (4) and provide it to the customer profitably.

The order in which one tests these hypotheses depends on their cost and number of dependencies, and we start from the cheapest and least dependent tests to perform.

Leaders tasked with managing a business’ innovation portfolio should:

- Determine the capacity (number of ideas) that the portfolio will be able to handle given a period of time, based on resources available.

- Establish the initial criteria an idea needs to fulfill to be accepted into the portfolio, such as the minimum of a 10x ROI, in addition to other organization specific strategic requirements.

- Set the budget in time and money each idea has to test its hypotheses at each stage.

- Create a knowledge base where ideas that are not pursued can be shelved for later reuse, as in the case of the adhesive used for Post-It Notes.

- Create the interfaces to engage with the rest of the organization and uncover previously overlooked knowledge.

Finally, the goal is not to push projects through the finish line, come what may. In fact, at a 10% success rate, the probabilities are stacked against any single one of them. Rather, it is about building a portfolio that follows a process that tests ideas, and builds knowledge continuously from which, after several iterations, a few 10x-ers that make the cost of the whole portfolio worthwhile will emerge.